| February 2007 Index | Home Page |

Editor’s Note: Dr Siccama conducted a literature research and studied four institutions to determine faculty and staff roles in developing and implementing online programs. She found there was significant collaboration between faculty and staff in course design, production, implementation and evaluation.

Work Activities of Faculty Support Staff

in Online Education Programs

Carolyn J. Siccama

USA

An instrumental and collective case study used qualitative research methods to explore the work activities of the professionals who occupy the role of faculty support staff in online education programs. Data was collected from four participants, over a four month period of time, in the form of one demographic questionnaire, two interviews, two site observations, twelve photographs and two Week in Review Activity Logs. Important to the structure and integration of the data collection, management and analysis was the use of QSR NVIVO®, qualitative data analysis software. Results show that the work activities of the participants include the management of the online course development and online course evaluation processes, initiation and facilitation of discussions with faculty about teaching online, building professional relationships with faculty and promotion and creation of networking opportunities among faculty who teach online.

Keywords: qualitative research, online education, faculty support staff, NVIVO, distance learning, work activities, online programs

Introduction

An instrumental and collective case study used qualitative research methods to explore the work activities of the professionals who occupy the role of faculty support staff in online education programs. Data was collected from four participants, over a four month period of time, in the form of one demographic questionnaire, two interviews, two site observations, twelve photographs and two Week in Review Activity Logs. Important to the structure and integration of the data collection, management and analysis was the use of QSR NVIVO®, qualitative data analysis software. Results show that the work activities of the participants include the management of the online course development and online course evaluation processes, initiation and facilitation of discussions with faculty about teaching online, building professional relationships with faculty and promotion and creation of networking opportunities among faculty who teach online.

Keywords: qualitative research, online education, faculty support staff, NVIVO, distance learning, work activities, online programs

Introduction

In the traditional model of classroom based instruction in higher education, the responsibility for the design, development and delivery of courses has remained solely with one person, the faculty member (Boettcher & Conrad, 1999). Once faculty enter the realm of online instruction, they quickly realize that they can no longer design and develop their courses alone. Courses that are delivered in online environments require different types of design and development support than do traditional face-to-face courses and it is highly recommended that faculty consult with professionals who are knowledgeable in the technology and pedagogy of teaching online (Boettcher & Conrad, 1999; Hanly, 1998). Such support professionals have been referred to as the key ingredient and the fulcrum in online programs, however, little is known about the specific work activities and the role of these individuals within the context of online education programs (Crang, 2000; Fredericksen, Pickett, Shea, Pelz, & Swan, 1999). The roles of faculty support staff in online programs are considered to be new and emerging in higher education (Davidson, 2003; Gornall, 1999).

Within the past five years, there has been an interest in the study of work activities and roles of new professions in higher education. Research studies from the United Kingdom seem to be primarily informing this area of interest (Beetham, Conole, & Gornall, 2001; Conole, 2004; Oliver, 2002; Shephard, 2004). However, none of the studies emerging from the United Kingdom are specific to online education or distance education programs.

New and emerging roles of service and/or staff positions have been explored from various angles. The analysis of job announcements of instructional technology service positions and educational developers is one way that has been used to identify the types of jobs available and the associated responsibilities and qualifications (Surry & Robinson, 2001; Wright & Miller, 2000). Metaphors, or descriptions that relate the job to other, more commonly known, jobs are often used to describe emerging professions (Surry, 1996). Portfolios have also been used to document professional experience of faculty developers and educational developers and to provide a rare opportunity to chose how to define roles and responsibilities (Stanley, 2001; Wright & Miller, 2000).

There is also evidence that other professional fields are also struggling to define work activities and roles for professions that are new and emerging in higher education. Disciplines such as library science (Goulding, Bromham, Hannabuss, & Cramer, 1999; Law & Horne, 2004; Rapple, Euster, Perry, & Schmidt, 1997), nursing (Sebastian, Mosley, & Bleich, 2004), educational technology (Davidson, 2003), corporate training (Aragon & Johnson, 2002), educational development (Wright & Miller, 2000), information technology (Thompkins, Perry, & Lippincott, 1998) and instructional technology (Guernsey, 1998) have clearly documented the challenges they face in defining new roles in their respective disciplines.

Specific to online and distance education, studies have attempted to identify broad categories of roles (Hanrahan, Ryan, & Duncan, 2001; Wright & Miller, 2000), identify lists of the most important roles in distance education (Thach, 1994; Williams, 2003), use anecdotes to describe roles (Fredericksen et al., 1999) or identify conceptions of roles (Inglis, 1996). It is not until we know about the work activities, or work content, of the professionals who occupy roles of faculty support staff we cannot begin to speculate about their roles (Mintzberg, 1973).

What’s missing is any literature to support the categories and perceptions which have emerged. Are the perceptions really an accurate indication of what these individuals do? Looking at studies of emerging roles across many different professions provided important insights into methods, techniques and challenges for this research study in defining and studying work activities.

Research Question

The research question shaping this study was: What are the work activities of the professionals who occupy the role of faculty support staff in online education programs?

Overview of Methodology

A qualitative collective case study approach was used as the research method to document the work activities of individuals who occupy the role of faculty support staff in online education programs. The unit of analysis was the content, or work activities, of the individual faculty support professional. Four professionals who occupy the roles of the faculty support staff within four different online education programs were studied. The 4 participants work at two or four-year postsecondary institutions in the northeastern region of the United States that offer asynchronous online courses (graduate or undergraduate) over the internet. Participants of the study were from institutions where the faculty members conduct their own course development, with the assistance of the faculty support staff, and there is an existence of a structured faculty support and training program for faculty who teach online.

The faculty support professionals who participated in this study work directly with faculty members in any or all aspects of online course planning, design, development and delivery. Three additional criteria used to select participants included those who work full-time, have a minimum of twelve months experience in their role conducting faculty support (Inglis, 1996) and, work in a support/service position versus a faculty position (Shephard, 2004).

By employing a collective case study approach (Stake, 1995, 2003) five types of data were collected: 1) demographic questionnaire, 2) interviews, 3) site observations, 4) visual data, and 5) Week in Review Activity Logs. Such variety of data collection techniques allowed me insight into their professional daily lives to aid in describing their work activities within their respective online education programs.

Data Management and Analysis with NVivo®

A data management strategy was established early within the NVIVO qualitative research software which allowed for frameworks to be established for data management, organization and analysis. This structure of data management allowed for simultaneous data collection and interpretation as the research process unfolded (Creswell, 1994). Richards (2004) documents four methods in which NVIVO can serve to ensure the appropriate data are used, the inquiry is thorough and the best possible outcome is achieved. These four methods, used extensively in this study to help assure validity and trustworthiness, include the maintenance of audit and log trails, interrogation of interpretations for sound inquiry, the scoping data and establishment of saturation for robust explanation.

Findings: Background of Participants and their Online Programs

The context and work environment within which the faculty support staff work plays an important role in the type of work activities they conduct.

Background of the Participants’ Online Programs

Defining the work activities present in online education in higher education varies depending on the institutional environment, particularly related to the distance education model being implemented (Clay, 1999; Smith, 2004; Williams, 2003). Two main categories of information emerged that illustrate a 1) general overview and background of each of the four online programs (see Table 1) and, 2) the institutional approach to course development and training (see Table 2).

Background information related to online programs

Name | Institution | Age of online program | # certificates | # courses | # online degrees | Level of Program | Length of courses |

Sally | Maple State College | 1998 | 2 | 40 | 3 | Grad and Undergrad | 14 weeks |

Lynn | Oak University | 1997 | 4 | 124 | 35 | Grad and Undergrad | 8 weeks 11 weeks |

Lisa | Willow Community College | 1999 | 1 | 72 | 2 | Undergrad only | 14 weeks |

Dina | Cedar College | 2002 | 26 | 49 | 0 | Undergrad only | 3 weeks to 12 weeks |

Table 2

Institutional approach to course development and training

Name | Course Expectations Prior to Teaching Online | Length of Training | Training Format | Learning Management System | New courses per semester or term |

Sally | Complete course online | 7 modules, 6 weeks | Self-Paced Online Tutorial, one-to-one, asynchronous instructor led | Blackboard | 1-2 |

Lynn | 1 week online | 8 weeks | Asynchronous instructor led One-to-one | Blackboard | 3-4 |

Lisa | Complete course online | 6 weeks online | one on one and asynchronous online | Blackboard | 2-5 |

Dina | Complete course online | Author: 4 weeks Instructor: 8 weeks | One-to-one, online showcase & print manuals, group sessions | Proprietary | 3-4 |

Background Information of Participants’

All 4 study participants were female, however, gender was not specified as part of the study criteria. All participants were Caucasian. Every participant had been working in their current position from two to four years. Three of the four participants had supervisory responsibilities in their current positions, supervising both full and part time staff and student staff

In regards to education, all four have Master’s degrees. Professional development of each participant takes various forms. All participants aim to keep up to date and current on trends in the field of online education by reading print and electronic publications, joining professional organizations, joining email list serves and attending conferences. None of the participants have ever contributed articles to any of the publications that they read on a regular basis. A few participants are active members within various professional organizations such as the United States Distance Learning Association and the North East Regional Computing Program

Details of Participants Work Activities

Table 3 provides details on participants work activities that reflect “somewhat typical” weeks as documented by 7 of the 8 activity logs.

Table 3

Emails, Phone Calls, Meetings and Working Hours

Name | Week of Semester or Term | Email replied to | Email Received | Phone Calls received | Scheduled Meetings with Faculty | Unscheduled Meetings a | Worked Evenings? |

Sally | Week 9 | 147 | 83 | A few | 3 | 0 | Yes |

Week 14 | 250 | 275 | 7 | 0 | 0 | Yes | |

Lynn | Week 2 | 100 | 250 | 10 | 0 | 2 | Yes |

Week 7 | 150 | 250+ | 10 | 3+ | 0 | Yes | |

Lisa | Week 10 | 50 | 50 | 18 | 3 | 0 | No |

Week 15 | 90 | 110 | 38 | 1 | 6 | No | |

Dina | Mid to near end of term | 79 | 117 | 12 | 1 | 5 | Yes |

In between terms | 94 | 122 | 12 | 0 | 2 | No |

a Unscheduled meetings are informal meetings that take place in the hallway, restrooms or when someone drops into their office looking for assistance.

Findings

Five findings emerged as a result of the data analysis.

1. Managing the Process of Online Course Development

Faculty support staff work with many different types of faculty at any one time. In managing the course development process, they are managing, organizing, and keeping track of the progress of faculty who are at various stages of online course development.

The spectrum of faculty that the faculty support staff may work with or keep track of at any one time is very broad including faculty interested in teaching online, potential faculty

Various strategies are used to manage the logistical details that are inherent in such complex systems such as timelines, checklists and meetings.

Timelines and Checklists

It was very interesting to find that all 4 participants have created and use some type of timeline or checklist to share with faculty. Such tools are given to faculty to help them to better understand the various milestones or action items expected of them during the online course development process, and as a way for faculty to help manage and plan their own course development progress.

Meetings become an important way to manage the online course development process. Depending on the model of the online education program and the type of training that is offered, two different types of meetings were reported, 1) meetings with faculty and, 2) meetings with staff. The meetings that the faculty support staff have are not always in the traditional format of sitting down at a table and meeting. The visual data provided powerful images that allowed unique insights into the work activities of the faculty In managing the course development process, there is much technical and system administration work that happens, as Sally notes, “behind the scenes”. Faculty may or may not be aware of the work done behind the scenes, but it is a very important part of supporting faculty in their online course development process. All 4 participants report that part of their work involves managing relationships with Blackboard and/or in the case of Dina, she works closely with her technical team to improve, build and update their proprietary Learning Management System support staff. For example, Figure 1 shows a picture that Lisa took of a hallway and noted that a lot of her meetings, conversations and consultations occur in this hallway.

Figure 1. Lisa’s Hallway

Working with such a diverse groups of faculty is not without its challenges. Early in the course development process Lisa finds that sometimes there is confusion about her institutions’ nine month timeline and expectations for developing an online course. During the training component of the online course development process, many challenges seem to emerge. Lisa shares that she has had problems with faculty retention in the online course because they may get discouraged while taking the online course. She is hoping that meeting with them one time during her newly revised six week training course will help address the faculty retention issue. It is challenging for Dina to work with difficult authors (faculty) who don’t follow the agreed upon course development deadlines. Lynn’s challenges are more around institutional policy issues. “We don’t offer development money, but at the same time it is a best practice to really have that class developed before” the term begins

Work Activities behind the Scenes

In managing the course development process, there is much technical and system administration work that happens, as Sally notes, “behind the scenes”. Faculty may or may not be aware of the work done behind the scenes, but it is a very important part of supporting faculty in their online course development process. All 4 participants report that part of their work involves managing relationships with Blackboard and/or in the case of Dina, she works closely with her technical team to improve, build and update their proprietary Learning Management System.

2. Managing Course Evaluation Processes

The course evaluation process often takes place at the end of the semester or term, when online students have access to complete an anonymous course evaluation about the course they are completing online. A second theme that emerged, related to course evaluations, is the work that the faculty support staff do to solicit feedback related to the structure of their training approaches and training courses.

Online Course Evaluations.

The work that the faculty support staff do related to online course evaluations is varied. The support staff role within the course evaluation process may involve managing the logistics in making sure that the course evaluation gets posted at the appropriate time in the semester or term, they may do the actual data analysis of the evaluation results, and/or they are involved in making sure the results get distributed to the appropriate campus administrators and to faculty.

The faculty support staff actively solicit feedback from faculty about how they can improve their training programs. For example, at two points during her online training course Lisa solicits feedback from faculty on the structure, assignments, readings, content of the course, the experience, the facilitators and the strongest and weakest aspects of the course. As a result of this feedback, in addition to her observations, Lisa is revising her current training course by shortening it two weeks and instituting a mid-course meeting with faculty.

3. Initiating and Facilitating Discussions about Teaching Online

Faculty support staff are very involved in discussions about teaching online including, 1) Initiating Discussions and, 2) Facilitating Discussions with faculty. While these conversations are happening at many levels with higher education, it is the faculty support professionals who work directly with the faculty who are prompting and having many of these ‘front line’ conversations, both synchronously and asynchronously, with faculty.

4. Building Professional Relationships with Faculty

Interwoven within the descriptions of their work activities, each participant clearly described the importance of building relationships with faculty throughout the online course development process. The support staff clearly articulated some behaviors they enact when facilitating the support of faculty who are in the process of designing, developing and teaching online courses.

The professional relationships that staff develop with faculty is a delicate and negotiated role (Fredericksen et al., 1999), and the participants in this study recognize the importance of this role. There were two distinct points in time that are critical to the building of professional relationships with faculty. The first is the first contact with faculty and the second is all subsequent contacts with faculty. The first contact is defined as the first meeting or phone call that participants make with a new or potential faculty member who may teach online at their institution.

After the first contact there are many different types of behaviors that participants perform as a way to continue to build their relationships with faculty. Five categories were created “in vivo” which is defined by Richards (2005) as “categories well named by words people themselves use” (p. 95). The five categories include:1) make faculty feel comfortable, 2) listening, 3) meet faculty needs, 4) patience, and 5) follow through.

Making Faculty Feel Comfortable

Three of the four study participants used the term comfortable during the first interview when referring to how they like to make faculty feel when they are working with them. In particular, the points in time when the support staff aim to make faculty feel comfortable is right before and right after the semester or term begins, particularly those faculty who are teaching online for the first time.

Listening to faculty’s needs and concerns around the development and teaching of their online course is one way in which the faculty support staff build credibility and rapport with the faculty. Lynn specifically identified various ways she builds credibility and rapport with both full time and adjunct faculty, “for full time faculty it is meeting with them on staff, it’s talking with them what they think, listening to them, for our adjuncts it is having that first interview call where we talk and I listen to them”

The data suggest two categories in which the faculty support staff work to meet the needs of the faculty who are teaching online. They strive to meet the learning needs and the technology needs of faculty. All 4 study participants aim to understand how faculty learn and will adjust their teaching style to fit the learning needs of faculty. For example, Dina may go to the office of a faculty member to help them since it is easier for the faculty member to work and learn from their own computer. Lisa talks about “meeting them where they are and bring them along”.

Another important consideration when working with a faculty member who is developing or teaching online is to be able to meet their technology needs. Participants often spoke about finding out what the faculty needs are in relation to technology and getting them the resources, tools and support they need to meet their needs.

One behavior mentioned by all participants is patience. Participants described how they use the virtue of patience in the many different spaces in which they work including in person, over the phone or asynchronously during an online training course.

The importance of having patience with faculty especially in relation to technical issues was commonly mentioned. Sally talks about working with faculty to post materials into Blackboard, the Learning Management System used at her college. She noted that “if it takes all day, to post an item, or it takes five minutes, I am going to make sure that when they leave they are comfortable with whatever it was that they were trying to achieve.”(Sally).

Follow through is defined according to specific words or phrases that the participants shared with me such as “always being there”, “getting back to them on time”, “delivering on what you say you will do”, and “follow through” . It is through such actions that relay to the faculty that their specific institutions are serious about providing them adequate support staff and resources so they can effectively teach their course online. Such interactions may result in what Fetzner (2003) calls the unanticipated impacts of faculty support in online programs which is the building of credibility and rapport between faculty and staff.

5. Connecting Faculty to other Faculty

In addition to building professional relationships between themselves and the faculty members, faculty support staff spoke frequently about and provided evidence for how they promote and create networking opportunities, both asynchronously and synchronously, among faculty who teach online.

All 4 participants facilitate and/or provide access to some type of self-paced or instructor led asynchronous online training course which is required for faculty to complete prior to teaching online. Each of the training formats include samples and models of relevant course materials that have been developed by faculty at their respective institutions.

Lynn affirms the importance of connecting faculty with other faculty, especially “if an instructor is teaching face to face and needs to start developing and teaching online, the most powerful way for them to really start grasping it is to see what their peers are doing”

Even though a lot of the work that the support staff do with the faculty are online in the training courses or via email, there is still a strong existence of working one-to-one and face-to-face with the faculty. Participants often spoke about various workshops they have for faculty. Common characteristics of these workshops are they are informal, offer refreshments or lunch, and they are created so that faculty have an opportunity to talk and share their experiences. If the workshops are technology related they may be led by one of the support staff since it is more of a technology “training” session. If the topic of the workshop is pedagogy focused, the faculty support staff will often have faculty develop and/or facilitate the workshop. These may take the form of a show and tell, sharing a success story, or a specific topic related to online teaching, such as building interactivity into an online course.

Lynn and Dina both mentioned that if a faculty member is “having trouble grasping”

Looking Across the Findings: A Discussion

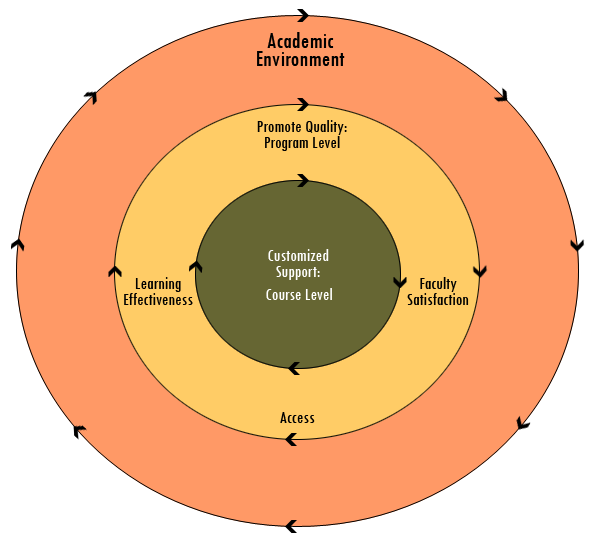

Three significant outcomes resulted in connection to my inquiry. The findings show evidence that the nature of the work of faculty support staff occurs at three distinct levels: 1) at the course level, 2) at the program level and 3) within an institutional environment.

Figure 2. Space within which faculty support staff

conduct their work activities

Figure 2 depicts an image that was constructed to visually represent the space within which the participants conduct their work activities, and also to represent the cyclical nature of their work.

The core of their work, as depicted by the inner most circle, takes place at the course level, providing support to faculty during any and all phases of online courses including training, planning, designing, development and delivery. The faculty support staff keep track of various nuances of each course and/or how each faculty member teaches their course. It almost becomes a type of customized support for faculty and this becomes a critical element in supporting the necessity of faculty support within online education programs. It is the faculty support staff who are the individuals who become most familiar with the courses, how they are set up, how faculty members teach their courses, and what tools they use. In another cyclical, but related, space is the cyclical nature of course development and evaluation process. Participants manage the online course evaluation process as a way to constantly strive for continuous improvement of their institutions online courses and program.

The middle ring of the circle depicts another layer within which the support staff work - promoting quality at the program level. The faculty support staff work at various levels to promote quality in areas such as promoting online interaction, having comprehensive approaches for evaluating courses, providing appropriate learning management systems, building in opportunities for faculty to share their experiences, practice and knowledge, and providing technical support and training.

The five types of data collected in this study provided clear evidence that the faculty support staff promote quality in three of the Sloan Consortium five pillars of quality including, 1) learning effectiveness, 2) access and, 3) faculty satisfaction (Moore, 2005).

The outer ring of the circle depicts the academic environment within which the faculty support staff work. The work of the faculty support staff ebbs and flows within the cyclical nature of the semester or term, and meeting faculty needs at various times throughout the semester or term. In talking about the cyclical nature of her job, Sally refers to the type of questions she handles depending on the time of the semester “that the type of questions may change, but the activities still need to keep going,” and “it just keeps going round and round and round.”

Conclusion

The work of the faculty support staff has far reaching implications within their respective institutions as they work closely with not only faculty, but with colleagues, administrators and students to build and grow the number of courses and their respective online education programs. The individuals who occupy the roles of faculty support staff in this study understand online education. They are in unique roles that require an understanding of the broader issues related to online education and the data suggests that they do understand the complexities inherent in online education. Parallels can be drawn to what Gornall (1999) identified in her research on new professionals in higher education, that their roles can be regarded as marginal, yet powerful, in they can be associated with institutional change and long term institutional strategy.

References

Aragon, S. R., & Johnson, S. D. (2002). Emerging roles and competencies for training in e-learning environments. In Advances in Developing Human Resources (Vol. 4, pp. 424-439): Sage.

Beetham, H., Conole, G., & Gornall, L. (2001). Career Development of Learning Technology Staff: Scoping Study Final Report: University of Plymouth.

Boettcher, J. V., & Conrad, R.-M. (1999). Faculty guide for moving teaching and learning to the web: League for Innovation in the Community College.

Clay, M. (1999). Development of training and support programs for distance education instructors. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 2(3).

Conole, G. (2004). The role of learning technology practitioners and researchers in understanding networked learning. Paper presented at the Networked Learning Conference, Sheffield.

Crang, R. (2000). Review: Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with asynchronous teaching and learning in the SUNY learning network. Paper presented at the 1999 Sloan Summer Workshop on Asynchronous Learning Networks, Urbana, IL.

Creswell, J. W. (1994). Research Design: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Davidson, J. (2003). A new role in facilitating school reform: The case of the educational technologist. Teachers College Record, 105(5), 729-752.

Fetzner, M. J. (2003). Institutional support for online faculty: Expanding the model. In J. Bourne & J. C. Moore (Eds.), Elements of Quality Online Education: Practice and Direction (Vol. 4). Needham, MA: Sloan-C.

Fredericksen, E. E., Pickett, A. M., Shea, P. J., Pelz, W., & Swan, K. (1999). Factors influencing faculty satisfaction with asynchronous teaching and learning in the SUNY learning network. Paper presented at the On-Line Education: Learning Effectiveness and Faculty Satisfaction, Urbana, Illinois.

Gornall, L. (1999). 'New Professionals': Change and occupation roles in higher education. Perspectives, 3(2), 44-49.

Goulding, A., Bromham, B., Hannabuss, S., & Cramer, D. (1999). Supply and demand: The workforce needs of library and information services and personal qualities of new professionals. Journal of Librarianship and Information Science, 31(4), 212-223.

Guernsey, L. (1998, December 11). A new career track combines teaching and academic computing. The Chronicle of Higher Education, A35-A37.

Hanly, B. (1998). Online ed 101. Retrieved December 12, 2002, from www.wired.com/news/news/email/explode-infobeat/culture/story/15061.html

Hanrahan, M., Ryan, M., & Duncan, M. (2001). The professional engagement model of academic induction into on-line teaching. The International Journal for Academic Development, 6(2), 130-142.

Inglis, A. (1996). Teaching-learning specialists' conceptions of their role in the design of distance learning packages. Distance Education, 17(2), 267-288.

Law, M., & Horne, A. (2004). Bringing users and "stuff" together. Feliciter, 2, 51.

Mintzberg, H. (1973). The Nature of Managerial Work. New York: Harper & Row.

Moore, J. C. (2005). The Sloan Consortium Quality Framework and the Five Pillars. Retrieved February 7, 2006, from http://www.aln.org/publications/books/qualityframework.pdf

Oliver, M. (2002). What do learning technologists do? Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 39(4), 245-252.

Rapple, B., Euster, J. R., Perry, S., & Schmidt, J. (1997). The electronic library: New roles for librarians. CAUSE/EFFECT, 20(1), 45-51.

Richards, L. (2004). Validity and Reliability? Yes! Doing it in software. Paper presented at the Strategies Conference, University of Durham.

Richards, L. (2005). Handling Qualitative Data: A Practical Guide. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Sebastian, J. G., Mosley, C. W., & Bleich, M. R. (2004). The academic nursing practice dean: An emerging role. Journal of Nursing Education, 43(2), 66-70.

Shephard, K. (2004). The role of educational developers in the expansion of educational technology. International Journal for Academic Development, 9(1), 67-83.

Smith, E. S. (2004). Considerations of rank and niche in distance education. Online Journal of Distance Learning Administration, 7(3).

Stake, R. E. (1995). The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stake, R. E. (2003). Case Studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Strategies in Qualitative Inquiry (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Stanley, C. A. (2001). The faculty development portfolio: A framework for documenting the professional development of faculty developers. Innovative Higher Education, 26(1), 23-36.

Surry, D. W. (1996). Defining the role of the instructional technologist in higher education. Paper presented at the Mid-South Instructional Technology Conference, Murfreesboro, TN.

Surry, D. W., & Robinson, M. A. (2001). A taxonomy of instructional technology service positions in higher education. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 38(3), 231-238.

Thach, E. C. (1994). Perceptions of distance education experts regarding the roles, outputs, and competencies needed in the field of distance education. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Texas A & M University.

Thompkins, P., Perry, S., & Lippincott, J. K. (1998). New learning communities: Collaboration, networking, and information literacy. Information Technology and Libraries, 17(2), 100-106.

Williams, P. E. (2003). Roles and competencies for distance education programs in higher education institutions. The American Journal of Distance Education, 17(1), 45-57.

Wright, W. A., & Miller, J. E. (2000). The educational developer's portfolio. The International Journal for Academic Development, 5(1), 20-29.

About the Author

Carolyn Siccama, RD, Ed.D., is the Distance Learning Faculty Coordinator in the Division of Continuing Studies and Corporate Education at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. While in this position she assisted in the initiation of the University’s Online Teaching Institute, which provides higher education faculty with an orientation to teaching online. In 2005, Carolyn was part of the Continuing Studies team which won two awards from the Sloan Consortium in recognition for excellence in online teaching and learning for their Online Teaching Institute and Institution-Wide Online Teaching & Learning Programming.

Dr. Carolyn Siccama

Distance Learning Faculty Coordinator

University of Massachusetts Lowell

Lowell, MA